By Ben Langlotz

|

January 10, 2020

|

Marketing

|

0 Comments

HOW TO GET YOUR CUSTOMERS TO PAY YOU TO SELL TO THEM

My favorite conversation starter at a dinner table with a client and their key employees (who are usually sick of talking to each other about work) is: “So, what do you like to do outside of the gun world?” These folks who’ve worked together for years sometimes end up learning interesting new things about each other, and I’m invariably reminded about just how interesting the people in our industry are. I have a special soft spot for the “geek” who acquires extraordinary expertise on one narrow area (as half the industry including me did with guns before joining the industry).

In recent years, I’ve transformed my childhood enthusiasm for astronomy and decades of owning a single little Questar telescope into being the nation’s top self-taught amateur restorer of those scopes, video instructor of restoration techniques, and something of a collector. The factory has been making them since 1954 and they consider me one of their best customers even though I’ve never bought a new one from them – just parts.

No turning back now

In the past few months, my optics enthusiasm that I bring to clients like Leopold led me to give in to another impulse: understanding how camera lenses really are put together and work. I recall decades ago when I became a gun nut I couldn’t resist taking apart any new gun I acquired to learn everything about it. I did plenty of gunsmithing on guns that didn’t need it. It didn’t take long for that young patent attorney to realize maybe he should try to apply his new technical knowledge to the firearms industry.

With camera lenses, I simply Googled to see if there were any “How to dismantle camera lenses” videos, and found the blog of a guy in Japan who collects and restores classic manual focus Nikon camera lenses, from the era when they were made of metal and built like a tank. For scores of lenses, he describes the process and pitfalls, with photo illustrations of key steps.

With decent-condition lenses I could buy on Ebay for $20-50, and with less than $100 of special tools to supplement my Brownells sets (like Japanese JIS standard not-quite-Phillips head screw drivers), I started a new hobby that’s inexpensive even compared to a little weekend plinking. I risked $40 on my first lens, and learned as much in a week of evenings as in a semester of trade school. And the lens worked – better than before (aside from a few internal cosmetic embarrassments that only a future repairer will discover). Even when the lens turned out to be a different model than in the blog, I did my best and guessed right most of the time. It’s like my childhood compulsion to solve those little mechanical puzzles, each with its own “trick” and only one way to get it right. I learned some unforgettable lessons:

- When you can force something and when you can’t.

- When something seems not quite right, it probably isn’t.

- There’s no lens component that requires filing or sanding to refit – you’ve probably switched some screws.

- No, you won’t remember all the disassembly steps you did in sequence when reassembling.

- Good photos, good videos, and good notes are essential “breadcrumbs” to find your way home.

- If it’s a total failure, it’s only $40 for a valuable lesson.

- Multi-start threads mean 15 ways to install it wrong, and one to install it right. Two sets of those mean 255 ways to get it wrong.

- Scraping sounds don’t go away eventually.

- Cleaning more won’t make it cleaner. Clean enough is clean enough.

- They don’t make ‘em like they used to.

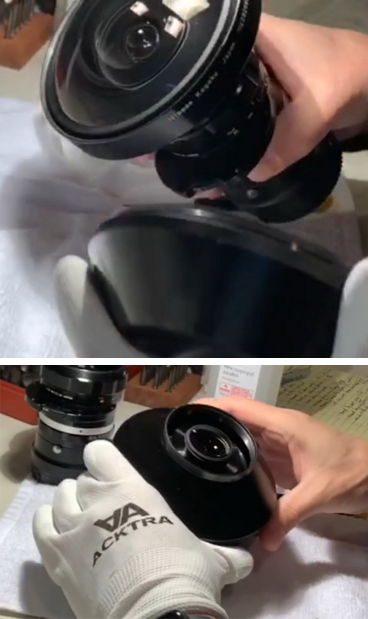

My graduation was my fifth lens. This one cost real money on Ebay – an exotic fisheye with a front glass element as big as a grapefruit. This one I acquired a few months earlier before starting this crazy lens hobby – not as a training tool, but for my use and collection. It turned out to have some foggy internal elements including the internal filter wheel, and the quote was about $300 to have it professionally cleaned. But I decided that I’d first see if I could develop the confidence to work on this one without any blog guidance or manual.

The big eye

After five successful projects, I felt ready to jump in and take a stab at “the Big Eye.” It all went well, cleaned up beautifully, and over dozens of hours I saved $300 in service costs (and had some fun). I took the time to make a video of the process, including my confused and hesitant speculations and wrong turns. I didn’t take the time to edit it, so if you find it at questarzone.com, it’s needlessly long – more than an hour.

The ending of this story is that I sold the lens for the same premium I would have paid in repairs – I got paid at professional prices (not hourly rates). The reason I sold it brings me to my next story. After decades as a loyal Nikon owner, I switched to Canon. Twice.

Jumping Ship

I’m a big fan of the new mirrorless cameras, and am convinced that they will obsolete DLSRs and their prisms and flipping mirrors. I loved my Nikon Z6, but was disappointed with the lens family, and envious of the Canon lens family and its innovative designs for the new mirrorless line. I tried the Canon once, and was horrified to learn that it zoomed “the wrong way.” I found it irritating, and the lens had some extra controls that I kept screwing up. Shooting was no fun. So I sent it back.

The Canon lens family kept nagging at me, and they released a must-have lens 6 months later that drove me crazy. I finally relented and bought the same Canon camera again – this time determined to learn and like it (it takes months to get used to a camera even with a familiar brand, and this was much worse with an unfamiliar one.) But the lens was the reward, and it was worth the growing pains and adjustments. I even came to appreciate that Canon lenses screw on the intuitive righty-tighty way that I never realized kept screwing me up the backwards Nikon way.

A Big Difference Between Brands And The Lesson It Taught Me

I’d never needed to service a camera or lens, so was never much influenced by the reviewers who griped about crappy Nikon customer service and raved about the excellent Canon service. But one lens I bought seemed noisier at focusing so I thought I’d see how good or bad the Canon customer service turned out to be.

The lady was cheerful, knowledgeable, and comprehensible. She patiently listened as I made lens focusing sounds on the speakerphone, and acknowledged my concerns without seeming phony. She invited me to send the lens in to be looked at for no charge. It turned out from online forum advice the lens was fine, and they could have advised me about one camera setting that aggravated the non-problem, but that didn’t bother me.

What really impressed me was how she engaged me in conversation about my interest in photography, learned that I had just made a big brand switch, and would be gearing up in the months ahead. She said “it sounds like you’ll want to know about our Canon Professional Services program.” Beautiful presumptive selling! She treated me like an industry professional, she presumed I have big bucks to spend on their lenses, and she didn’t question whether I’d even qualify for the VIP program.

Who Are Your VIP Customers?

As a wanna-be hobbyist I’d heard about these VIP programs, and secretly lusted to qualify, let alone to be invited. I recalled chatting with famed SR-71 pilot and author Brian Shul about cameras years ago and being more impressed by his Nikon Professional Shooter card than his speed records. The deal is amazing. For them – and this is the model I wonder if any of my readers have considered to build brand loyalty.

I pay them $300 per year, but only if I have enough Canon equipment to earn the points to qualify. To qualify for this level, you need to own several top-tier custom scoped rifles worth of gear. Thankfully my Nikon gear sales funded the transition.

I have to register all my equipment with them by serial number to prove that I “qualify” – so now they know everything about their customer. I get discounts and free shipping on service, which I never seem to need. I get a “free” lens strap – not sold in stores.

My favorite part is that I can request them to send me equipment for evaluation with no charge for shipping, and a week to play with them. As I’m editing this paragraph, the FedEx guy just dropped off a $2300 lens. It’s a good way to pick the right next lens, but mostly just fun. Also handy for hobbyist banter (“yeah I tried that one…”) There’s no more effective sales tool than an extended test drive. And they know exactly what products their customers are considering.

But not only does the VIP program provide valuable market data and help to sell, it intensifies customer loyalty.

I have to add one more thing: as I was increasing my ownership “points” to qualify for the next level, it actually motivated my decisions of what to buy. I don’t think it changed anything, but it was a real consideration in each decision, and might have accelerated my acquisitions. I also have to add that I have no illusion that there’s anything sensible, rational, analytical, or logical about this membership on my end. No, it’s all emotional. Like most of your customers’ decisions even when you and 90% of them would deny it. As emotional as “Ford vs. Chevy.”

My question for firearms industry executives is whether a VIP program might add enough value for your customers that they’ll actually pay you to market to them this way? I know every gun bunny wants to be a “sponsored shooter” and get free stuff, but why not have something for the aspiring competitor that feels the same?

Even as I know there are real pros that Canon just sends free stuff to, it still feels good to tell myself that I’m one of them at least superficially. Imagine offering your customers a “Sponsored Shooter Program” (SSP) membership that got them a Spandex jersey, direct buy discounts, first crack at new products, test and evaluation opportunities, and the works, for which THEY pay YOU. All while your actual sponsored shooters are getting the same free stuff all the wannabees are begging for. Add in factory tours, and invitation-only hunting/shooting/travel packages (profitable for you) and it could be irresistible to your most valuable customers.

You’re probably wondering about now: “When’s Ben going to introduce his own VIP program?” And you’ll be disappointed. I hope all my clients feel like VIPs, and if there’s any way I can enhance the experience, just let me know. Free T-shirt?