By Ben Langlotz

|

July 6, 2023

|

Books & Resources, Business, Firearms, Firearms Industry Advice, How To, Patent

|

0 Comments

HOW TO SEARCH PATENTS FOR GUNS AND FIREARMS TECHNOLOGY

There are a lot of good reasons why my firearms industry clients and other clients want to do a patent search. Sometimes, they’ll hire me to the do the job, but I’d like to offer a reliable resource for doing it yourself. Some patent searches are too formal for do-it-yourself internet work, even by me. In extreme cases, finding the “smoking gun” patent that wins a lawsuit can be worth tens of thousands of dollars invested in a search specialist (someone I would outsource the project to). In some cases, investing a couple thousand dollars in a formal patentability search makes sense before investing in a patent application, but most of my clients are satisfied they know their technology awfully well, and don’t need a formal search to tell them what’s been done before in their specialized area.

A simple patent search you can do yourself or we can do quickly and affordably can answer some important questions:

- What patents does my competitor have?

- Is this product patented?

- Is my invention patentable?

- What are the different inventions in this category?

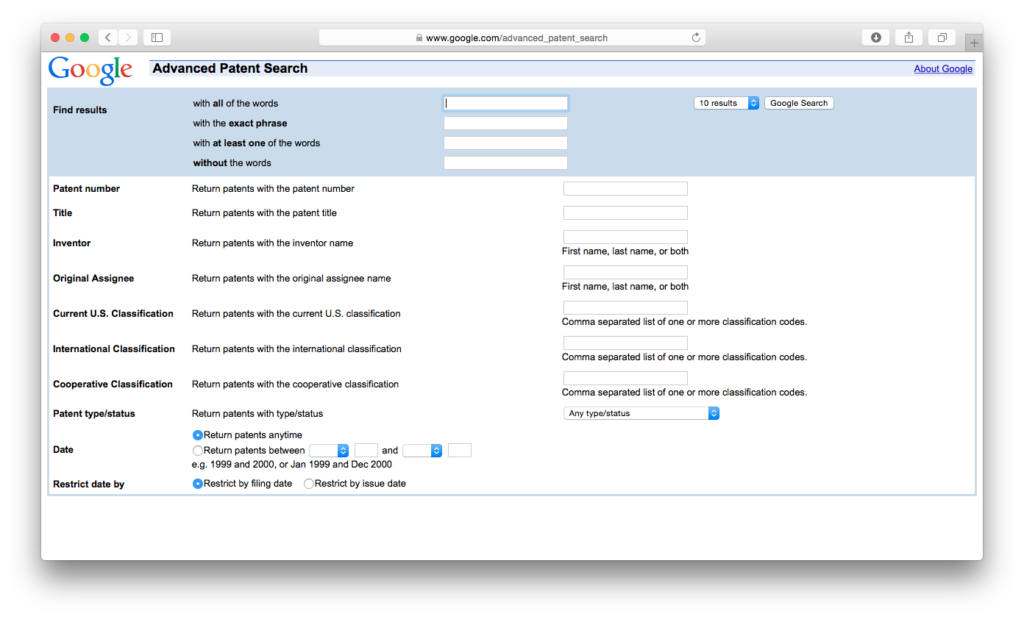

I use Google’s Advanced Patent Search for most of my searching. It has a much better interface than the Patent Office website (Imagine that, a commercial enterprise serving the customer better than a government one!)

Google Advance Patent Search

Patent Number

When you see a patent number on a product, and you want to read the patent, just enter the patent number in Google’s “Patent Number” field and you’ll get what you’re looking for. Sometimes, you’ll also get other patents or applications that refer to this patent, which can be useful. More on that below.

Owner/Company

Often a client will tell me they want to introduce a new product that competes head-to-head with a recent product from a competitor. But they’re worried that the competitor’s product might be patented. I first suggest that they get one of the products, and examine it and the product materials for a patent number or at least the words “Patent Pending.” It would be foolish for them to have a patented product and not tell the world about it, but it does happen. So, we search for any patents by that company. In patent language, the company that the inventor assigned the rights to is called the “Assignee”, so you can enter the name of the company in the “Original Assignee” field (which tells what company owned the patent at the time it was issued). But be careful, because while Remington might appear to be the owner, the actual assignee might be a holding company like “RA Properties.” Don’t trust results that don’t meet expectations. If your search says that Remington doesn’t have any patents, you’re probably using the wrong assignee name. One tip is to try to find a patent you know they own (maybe it’s listed on their website) and check that patent for the assignee.

Inventor

Where there isn’t any company, and the inventor has held his own patent rights, we can identify the inventor. This is also a good trick for finding the names of assignees, when you know the name of one key inventor. It’s also a good way to be sure you found all the company’s patents, because some companies can be sloppy about assigning every patent as they should.

Title

If you simply want to see what’s been invented (maybe to learn if your invention is patentable), you can try searching patent titles. If you’ve invented a gun that has a tunable whistle sound as the gas escapes (to help audibly identify friendlies), you might search “Firearm gas system with sound emissions.” But the problem is, even if that was patented, the patent attorney might have given it a different name, like “Musical Rifle” or “Identifiable weapon system” or “Firearm with acoustic indicator.” Or (heaven forbid): “Gun.”

Title searching can be good if you’re feeling lucky, and can open the door into the search process, but it can be unreliable.

Advanced Word Searching

For this, we use the top section of the advanced search page, and can search the entire patent document. Of course, this means we’ll have more hits to review, but you’re less likely to miss something. We have the power to add different words and phrases so we can find results “with all the words”, “with the exact phrase”, “with at least one of:” and “without the words”. If you’re used to advanced Google searching, this should be familiar.

I might search for patents with the exact phrase: “gas system” and any of the words “music tone sound pitch.” This will probably bring up lots of junk, but it’s a better way to be exhaustive. Tip: after you search, look at the search line above, and see how Google translates your search into its language. It’s easy to decode, and can help you craft searches. (E.g. ‘”gas system” music OR tone OR sound OR pitch’)

Filtering the Junk

You can filter your results by date, issued patents vs. applications, and patent types. It can be confusing when you see lots of foreign documents come up, and remember that one patent you’re looking for may have a corresponding published application and some foreign publications, too.

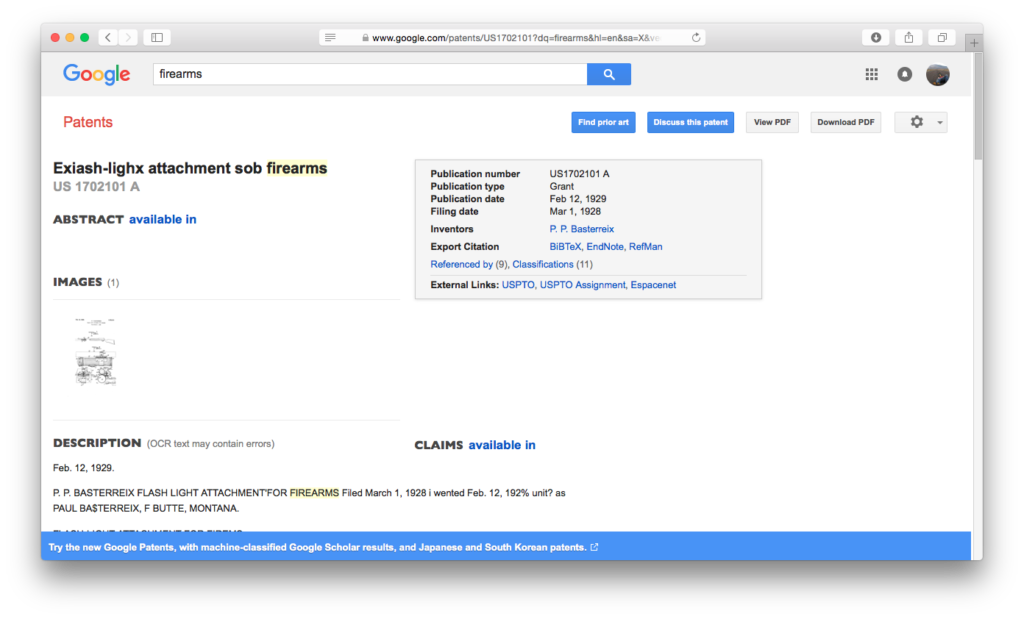

Follow the Trail

Your search results will include a list of patents. Click on one, and it will open up a page for that patent (there’s a pdf download button in the upper right). On the page that opens up, there’s a wealth of secret information that most people don’t know about. In the blue box in the upper right, there are clickable links. You can click the inventor name to see all his other patents. You can click the Assignee to see all their patents. If it’s a patent, you can click the published application, and you can also click external links to see the same patent in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office search system. The “USPTO Assignment” link will help you to find out if the patent is owned by a different company than before.

Patent Search Result

But the most important links for the next type of patent searching are the “Patent Citations” and “Referenced By” links. Patent Citations list all the patents and other documents that the applicant’s attorney submitted with the application, and all of the ones the patent examiner thought were relevant to the application (and maybe used in his rejections). “Referenced By” gives you all the later patents that thought that this one was relevant, and cited it. So these two links give you a look into that patent’s past, and its future. When you find a patent that seems relevant to what you’re looking for, you should dig into the past and future. Maybe one or two of the past patents have the key feature that you care about. Note those, analyze them, and then do this same process to look at their “ancestors” and “offspring”. Keep doing this until you find yourself covering the same ground. At this point, you may have done an excellent patent search, and gotten the results you needed. But you don’t know if there was some “circle” of other patents that never got cited by the ones you were looking at, so you want to keep looking.

Declassifying the “Classification” System

U.S. patents are categorized into hundreds of categories, and tens of thousands of subcategories. It’s like an old library system for cataloguing books. And it was created over generations by the government, such as it is.

When you view a patent on Google, up in that important upper right box you’ll have a link to “Classifications” that will take you down the page to some code (also found on the front page of the official pdf publication) that might look like: “102/506, 102/508”. Each of these slash-separated number strings is a U.S. Classification (ignore the foreign ones). Each class is a clickable link, and leads you to all patents in that class, which can be another goldmine. I advise that when you find relevant patents in your search, make a note of the classes, and search all those classes. It will probably be apparent that some classes are pertinent, and some relate to features that the examiner thought were important in that application, but aren’t relevant to your needs.

Classifications are where the professional searchers work. Patent libraries used to have “shoes” or boxes, each filled with the patents of a given subclass. The searcher could pull out the shoe, and flip through to see what looked right. That has some advantages over word searching, because there are some things that a trained pro can spot in an image that aren’t always easy to put into words (“the flange is at one end, unlike normal widgets that had the flange at the midpoint”).

Another great use of the classification system is for research as you’re developing products. I just had a client tell me that they’d like a comprehensive patent search of all patents for a particular type of arms product. I told them that it could be a $10,000 patent search, with the results delivered in several banker boxes, or I could give them a couple links to click, and let them delve into the hundreds of patents in that subclass, exploring, learning, and developing a better background in the field they were working in. Don’t forget that most patents (more than 20 years old) are expired, and their technology may legitimately be used by anyone as a safe haven against patent infringement.

What To Do With the Patents You’ve Found

You’ve succeeded in your patent search, and now you need to know how to interpret those patents. Does my new design infringe this one? Is my invention obvious over these patents? Should we disclose these along with my patent application? How do I read these claims?

Those questions could be covered in a stack of law books, or you might just give me a call, knowing you’ve saved a lot of time and legal fees by putting together the right information for us to analyze and answer your question. I look forward to hearing from you.