By Ben Langlotz

|

October 8, 2020

|

How To, Intellectual Property Advice, Patent

|

0 Comments

Stop the Worrying!

To SHOT or Not to SHOT?

Before I start the main story, I have to address what everyone is asking me about: Will there be a SHOT Show? My current take is that it might happen in some form but would be a faint shadow of its usual self, with many companies pulled out for the year, and many regular attendees skipping. Some data points I have heard but can’t confirm: No product handling – Everything under glass. Masks required – no lip-reading in a noisy environment. Clear barriers on conference tables – even harder to hear the person you’re talking to about confidential matters – easier for the eavesdropper behind? Companies pulling out because of liability and humanitarian fears of employees being infected – NSSF directors all face the same concerns. My worry: it’s hard enough to get a table at a restaurant or a seat at the bar in normal times – what will after hours life be like? Will it be room service every night? Also, I heard that they will limit attendees to 1/3 of normal – your favorite non-exhibiting, non-purchasing lawyer (who has donated tens of thousands in legal services to the NSSF) might well not even be allowed to attend. Good luck to us all.

Election note: The outcome will either be good for the nation or good for the industry – I’ll side with the nation, and the industry will do just fine.

Speaking of Worrying…

A typical marketing consultant would tell me I’m crazy to reveal the secrets in this month’s newsletter, but I have to be honest with my readers: Y’all worry too much.

The classic marketers say that the two greatest motivators are FEAR and GREED. Looking at today’s ads, SEX might seem to be another biggie, but when it comes down to it there’s either the fear of not having it (Charles Atlas ads with sand kicked in the weakling’s face), or greed for the wealth that can ensure a sufficient supply of it (just about all the other ads).

Still, you can probably safely dial down the fear, but only if you’re fully informed and on top of the legal deadlines, and the rules behind them. I won’t worry about greed here, because my clients are in business, and clearly looking to earn money and generate wealth. That’s a given. But with all the potential for devastating lawsuits and company-killing missed legal deadlines in the intellectual property world, I’m probably nuts to tell you to stop worrying so much.

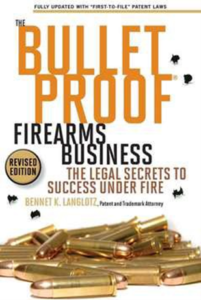

Helps you manage complex Intellectual property issues

FREE copy for subscribers like you available at gunpatent.com

My 400-page book “The Bulletproof Firearms Business – The Legal Secrets to Success Under Fire” is essential to help a firearms business executive manage these intellectual property issues. This article will summarize all the essentials, but readers are invited to get a free copy of the book, updated for the current First-to-File patent laws. (Your copy must have the “Revised Edition” medallion on the cover, or it’s dangerously obsolete – oops, I just used some “fear” in my urging you to get a freebie.)

I know, it’s not very profitable for me to send out so many free books, but I’m trying to make it up in “volume”. Plus, I think when firearm executives are better informed it makes our industry stronger, and I prefer my clients to come to the game well-informed, instead of after it’s too late to help.

Worry #1:

Fast First-to-File Fears

“We need to file this patent right away!” That’s what I hear most often from my clients. Maybe I did too good of a job informing my readers about the new First-to-File patent law change from a few years ago. Before then, we could calmly keep good inventor notebooks, and later prove whoever the first to invent something might have been. You didn’t even need to call your patent attorney to keep things secure. But now with First-to-File, whoever files first wins, which creates a powerful urgency.

Now, I want to share why that urgency might not always be so powerful. First, understand that filing simple “provisional applications for patent” (aka “Caveman Patents” – so easy even a caveman can write one) is normally the best strategy for the First- to-File legal environment. I’ve explained many times before how your informal write-up and drawings can be reviewed by me for adequacy, filed, and calendared. The works, all for a nominal charge that is fully credited forward to your eventual full patent application. That’s the sweet deal I created to make sure your rights get protected, even though Congress’ First-to-File law forced you to rush faster than you would have.

A Provisional application is never a bad idea, and not an expensive one. Sometimes, I’ll advise a client not even to spend anything on a patent search. Just file the provisional and secure the First-to-File date and worry later before making the larger investment in the full patent application whether to search. After all, a patent search is just an insurance policy against the risk that your invention might not be patentable, so that early “bad news” about patentability means: “Good news – you didn’t waste a bundle on the patent application!”

So, a provisional is a no-brainer, right? Well, almost. It’s an inexpensive insurance policy, but it insures against only one risk, which may be quite small in some instances. A provisional application is nothing more than “First-to-File insurance.”

To be clear, there are a bunch of good reasons you might want to rush a patent application filing. But the primary benefit of a Provisional is as First-to-File insurance. Here’s the scenario where a Provisional pays off: Say you’ve invented a new alternative to the Picatinny rail. It’s a radical system that’s easily machined from less material with less machine time. It provides infinite adjustments but has reliable return-to-zero precision. It’s cheaper to make than what it replaces, and it provides more benefits. So, you know you want to patent it.

The easy choice is to rush a provisional application. Cheap and fast. You can say patent pending, and not worry. But…Are you worrying too much? Is there really a risk that a competitor is about to develop the same thing, and become the First-to-File themselves?

If that happened, it would be VERY painful, because not only would you lose the chance to enjoy exclusive patent benefits for decades, but they would own the patent, and would be able to prevent you from producing your own invention!

You see, it’s the fearsome potential consequence that causes most sensible inventors to rush a provisional. But the fearsomeness of the consequence might be blinding them to the improbability. How likely it is that someone will invent the same thing?

If you’re working in a very competitive space where your competition is ferociously working to develop the same kinds of things as you are, then by all means rush. This is for the “hot” areas, like smartphone apps, aerial drones, and 3D printing. If Google and Microsoft are buying up small companies in the space, then every day can count, and you should rush the filing.

And I won’t say that gun technology is slow little backwater (my client list on the back cover is testimony to that), but if you came up with a new way to fold up a little pistol to make it fit in your pocket, you’re probably safe to assume that the competition isn’t in the midst of a crash development program to come up with the same technology.

Think of it this way: Did you conceive your invention in response to a new stimulus that would likely have triggered others to work on the same problem? If it’s an old stimulus (e.g. “rifle scope distance estimation is hard for newcomers to figure out”), then the risks are probably low. If there’s no stimulus, and you simply came up with the idea when in the bathtub, or at the range (or both in the case of one of my more eccentric and well-heeled clients), then you’re even safer. In contrast, the high-risk scenario is a new stimulus that might be triggering competitors to be inventing along the same lines. Worst case: a military agency has announced it’s looking for a new weapons system, and whoever develops the best system will get a fat contract (especially profitable if their winning proposal includes patented technology). A few years back it was precision modular rifles with folding stocks. Intensive development triggered by the same announcement led to dozens of new folding rifle stock patents. In our First-to-File system, the best strategy might be not to develop anything, but to gather a “think tank” to contemplate all the possible solutions, and to file a provisional that covers them all.

Then, proceed with development, knowing that your “big picture” provisional will predate all the competitors, who are waiting until their engineers have come up with a detailed design to talk to their patent attorney. Even if your “big picture” ideas don’t earn patents, they provide some defense against the possibility that others might get crazy-broad protection.

So, that big example of a flurry of inventive activity in response to a military contract illustrates how most inventions are very unlikely to face a big risk that someone else is working on the same thing, and will file before you do.

For most of my clients, the nominal investment in a provisional is less of a concern than the time it takes to collect some images, to write up a simple explanation of the invention, and to send it to me. (Now and then, a busy client will ask: “But Ben, I’m too busy. Can’t I just pay you to write the provisional?” To which I reply that we can do that, but then it ends up being a major investment in a full patent application).

Worry #2:

Won’t Someone Steal My Invention?

It’s possible, and it does happen, but it’s a rarity. Competitors want to steal your new invention probably about as much as schoolyard kidnappers want to take your bratty kids (just kidding – your kids are amazing and awesome).

I hear fretful complaints from inventors who are appalled to learn that the patent process can take a year or two, during which their invention is entirely unprotected. I assure them that infringement at the early stage is rare, and if it occurs, they should celebrate the proof that they have a real homerun of a new product.

Don’t worry about the short-term infringers. They’ll be “helping you make your market” for the short time until your patent issues, and once they’ve convinced their customers the product is essential, you’ll jump in after getting a patent and scoop up those customers (or charge a suitable royalty for the competitor to continue). In this example, the theft you feared is actually something to hope for. It’s the best sign of success.

Worry #3:

What About the Statutory Bar under 35 U.S.C. §102?!

Just kidding. No one worries about this kind of legal technicality. But you should. This is the rule that says that if your invention has been on the market for more than a year, you can’t get a patent. It’s too late. Patent rights are lost forever.

When I get a call from a new potential client eager to protect their new invention, one of the first things I ask is: “Has the product been on the market more than a year?” If so, I share the bad news, and the conversation quickly ends. I’m a little disappointed I didn’t get a chance to work on an interesting new project, they’re mightily disappointed that the core of their business is lost, and they feel like they’re to blame for not calling the lawyer soon enough. They vow not to wait too long net time, and I wish them well.

Thankfully, in this era of rushing to file provisional applications (sometimes rushing more than needed), the #3 disaster scenario is less common than it used to be. Maybe I should take a little credit in the firearms industry for raising legal awareness a bit, too.

If you’re not worried about competitors filing before you do, then you have lots of time to file a patent application. You can conceive an invention, develop it diligently for as long as it takes, then release it to the market. Within a year after releasing it to market, you need to file a patent application. This can be a provisional, giving you another year to invest in the full patent application (though I advise having a lawyer-drafted application within one year of market release in case the provisional has weaknesses).

This means you have plenty of time, and little reason to worry – at least about legal issues. You still have plenty to worry about in making the invention work and hoping that the market likes it.